With Batman Day at hand, we find ourselves once more reflecting on the singular phenomenon that is the Dark Knight.

There are plenty of reasons for Batman’s extraordinary longevity. His car. His costume. His origin story. They all play a role. But if Batman himself suspended me upside down over Gotham City by an impossibly thin strand of Bat-rope and demanded I give him an answer, the first thing that would spring to mind is his malleability.

“I’m whatever Gotham needs me to be,” Christian Bale’s Batman told Gary Oldman’s Jim Gordon in the final scene of 2008’s The Dark Knight.

Truer words were never spoken on any Earth in the DC Universe. For Batman is indeed what his city—and his fans—need him to be, as he’s proven countless times throughout his history. Vigilante, dad, lawman, clown, detective...the Dark Knight has been all of these and more.

When the world first encountered the Batman, in May 1939’s Detective Comics #27, he was introduced as a silent figure crouching on a rooftop, silhouetted against the moon, “fighting for righteousness and apprehending the wrongdoer, in his lone battle against the evil forces of society.” In his first story—and several that followed—his war on crime would pit him against those targeting the wealthy, his alter ego Bruce Wayne’s social class.

Initially inspired by pulp superstar the Shadow—another playboy by day, avenger by night—the early Batman brandished a gun and wasn’t above dispatching capital punishment to his foes. In his first appearance, he tosses one off a rooftop and punches another into a tank of acid, putting him at odds with the police.

His early persona makes sense. In the ’20s, America had seen crime skyrocket throughout Prohibition, leading to famed gangsters like Al Capone. The public wanted equally tough crimefighters. The Shadow and comic-strip police detective Dick Tracy (whose freakish rogues gallery would inspire Batman’s) were the heroes du jour. Both were introduced in the early ’20s, the final days of prohibition, and both fought crime with a deadly earnestness that helped readers sleep at night.

Shortly after Batman’s debut, however, the world changed. The Great Depression, which had put an end to Prohibition, was in turn halted by America’s entry into World War II in 1941.

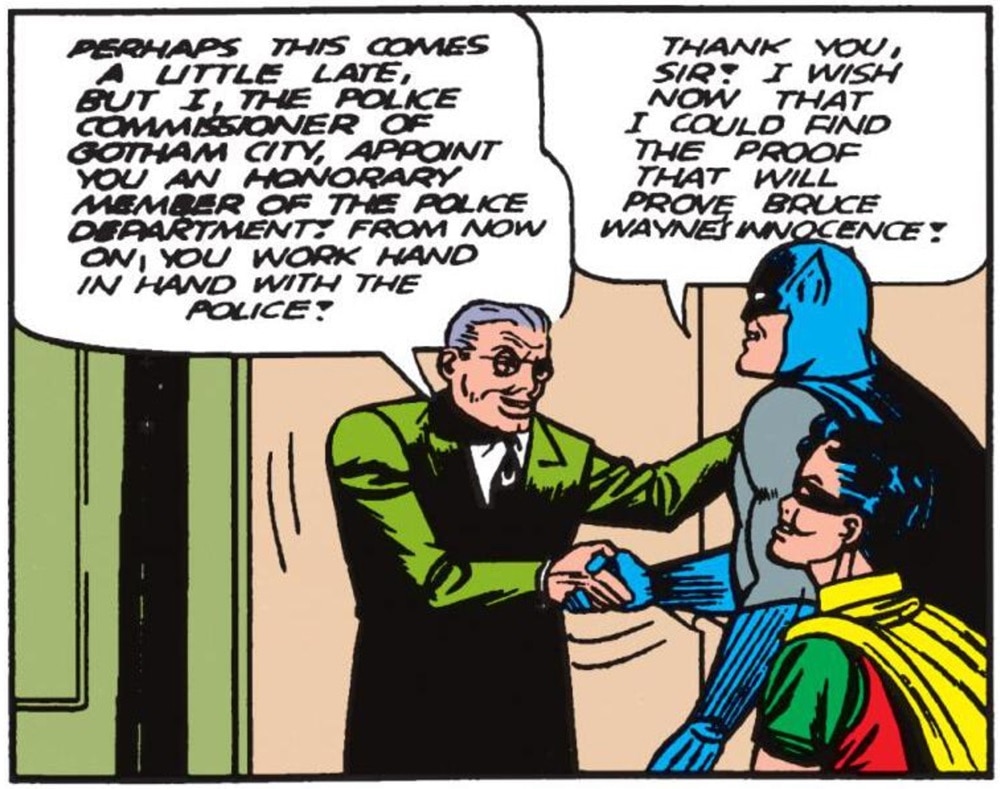

Just a year prior, in April 1940’s Detective Comics #38, Batman creators Bill Finger and Bob Kane (collaborating with inker Jerry Robinson) introduced Robin. The Boy Wonder humanized Bruce Wayne and brightened Batman's adventures. The Caped Crusader was now a big brother/father figure fighting for the little guy. A role model. Not only to Dick Grayson but to the millions of young readers who aspired to be Batman and identified with his ward. October 1941’s Batman #7 saw Batman deputized by Commissioner James Gordon. The Dark Knight now worked within the system, at a time when U.S. citizens most needed to believe in their government.

This incarnation of the Batman lasted throughout the ’40s, and grew even more lighthearted in the frequently sci-fi-flavored stories of the ’50s and early ’60s. The era culminated with the first live-action Batman TV show in 1966, starring Adam West as the Caped Crusader in eye-popping color. West played the Batman of the Golden Age comics so faithfully that his series quickly became the apotheosis of camp. It charmed non-fans, thrilled little kids and often incensed longtime readers who took their comics seriously.

Most Americans, however, needed a laugh. Following the Cold War paranoia that culminated in the Cuban Missile Crisis, President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in 1963. By 1966, the Vietnam War was well underway, and TV watchers wanted something as far as possible from the daily news headlines. The Munsters, I Dream of Jeannie and Batman did the job.

But escapism only lasts so long. When viewers tired of the joke, Batman’s TV audience shrunk as quickly as it had grown, and his comic sales slowed. Americans lost faith in the law and their government and began questioning the country’s involvement in Vietnam. Taking a chance on a different approach, young comics artist Neal Adams returned Batman to his roots as a grim nocturnal manhunter, albeit this time with a thirst for justice that took him beyond Gotham’s city limits. Adams introduced dangerous new foes like the monstrous Man-Bat and the James Bond villain-inspired global terrorist Ra’s al Ghul, co-created by writer Denny O’Neil. In the ’70s, O’Neil and Adams’ Batman was once more a vigilante who butted heads with the police. He functioned as such until the world again needed him to change.

By the mid-’80s, DC had decided to streamline its continuity and reboot its comics universe with the twelve-issue Crisis on Infinite Earths. By this time, the Vietnam War had ended and the Watergate scandal of the early ’70s had seen many Americans’ loss of faith turn into distrust. By 1986, in President Ronald Reagan’s second term, the Iran-Contra affair found that distrust erupting into outrage.

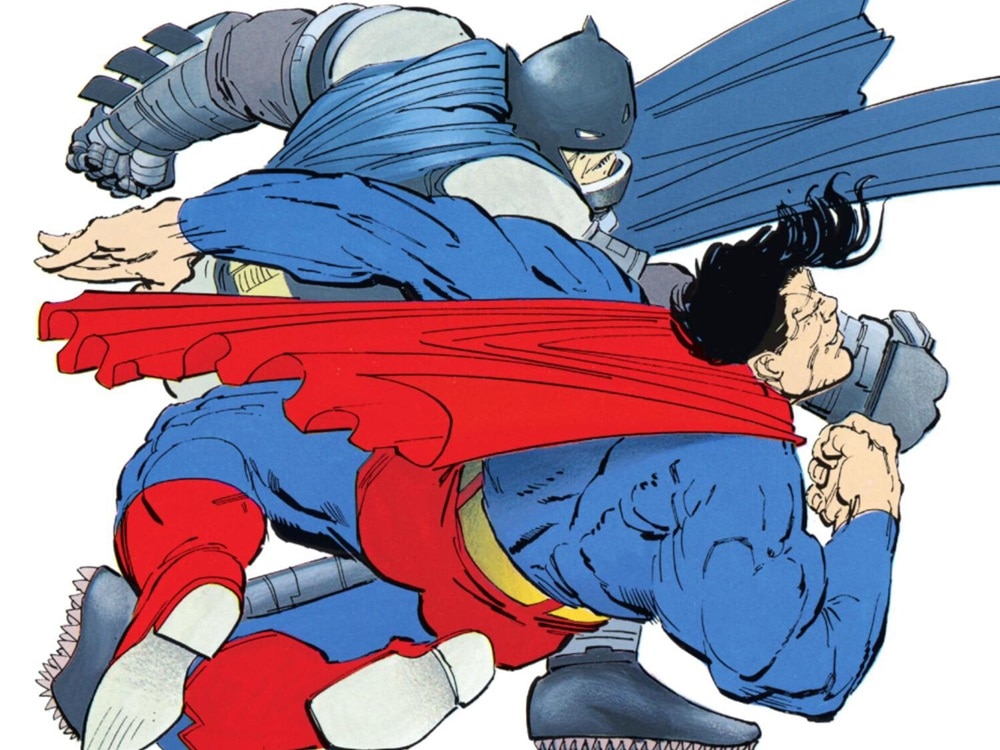

It was this anger that writer-artist Frank Miller seized upon when he introduced us to a post-Crisis middle-aged Batman in February 1986’s Dark Knight Returns #1. Mainstream American comics came of age that year, with Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ similarly politically charged Watchmen debuting in September. In December, Dark Knight Returns #4 depicted its hero battling a Superman ordered by Reagan himself to capture Batman. In the end, the Dark Knight, speaking truth to power, outwits the Man of Steel and takes his followers underground to continue his crusade.

A proto-Elseworlds story, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns was followed by Miller and artist David Mazzucchelli’s Batman: Year One, which launched a successful new canon for Gotham’s savior—one in which he continued to work outside the law. This was the true Golden Age of Batman, spawning classic tales like The Killing Joke and Gotham by Gaslight, the blockbuster Batman movies, Legends of the Dark Knight, Shadow of the Bat, Batman: The Animated Series, Knightfall, No Man’s Land, the Arkham video games and the Christian Bale-starring Dark Knight trilogy.

It’s the middle chapter of that trilogy—The Dark Knight—that best demonstrates Batman’s malleability. When he allows himself to be hunted as a criminal so Gotham can continue functioning in the wake of the Joker’s madness and its citizens can retain their faith in justice.

And yeah, his car’s pretty cool too. Happy Batman Day.

DC’s annual celebration of the Dark Knight is back! Batman Day is Saturday, September 20th. Click here for the round up of what’s happening and drop by our Batman Day hub for more news, comics and features on Gotham City’s greatest hero.

Joseph McCabe writes about comics, film and superhero history for DC.com. Follow him on Instagram at @joe_mccabe_editor.

NOTE: The views and opinions expressed in this feature are solely those of Joseph McCabe and do not necessarily reflect those of DC or Warner Bros. Discovery, nor should they be read as confirmation or denial of future DC plans.