Since 1938, Superman has been described as “Champion of the Oppressed.” As we celebrate Black History Month this February, it’s only fair to ask: do the Black readers and fans who look to Superman for a hero not deserve a Superman of their own? One who represents their own experience, perspective and dreams? The historic search for a Black Superman is a story told over decades, still being written today. In our previous installment, we took you from Richard Pryor in 1968 to the first Black Superman to appear in a comic. Today, let’s explore the rest of the story…so far.

1993: Historic Milestones

Since the debut of Black Lightning in 1977, more Black faces had begun to grace the covers of DC Comics. Characters like Cyborg in The New Teen Titans, Vixen in Justice League of America, and Amanda Waller in Suicide Squad had become indelible to the fabric of the DC Universe through the 1980s. And yet, behind those Black icons, there was always a team of writers and artists sharing an experience never authentically informed by their own lives. Heroes were becoming more diverse on the page, but the truth remained the same as it had always been before: after sixty years, the comic book industry as a whole was still overwhelmingly white. The lack of Black heroes wasn’t even the issue—it was the lack of opportunity for Black comic creators for a platform to tell their own stories and share their own experiences within the medium. And so, four Black creators, each titans in their own right, came together to try something new: a line of comic books and superheroes of their very own.

In March of 1993, Dwayne McDuffie, Denys Cowan, Michael Davis and Derek T. Tingle launched the first comic books under the branding of Milestone Media: Blood Syndicate and Icon. The story of Icon in particular is a superficially familiar one of an incredibly powerful alien who falls to Earth and adopts it as his home. But it’s the differences in telling by writer Dwayne McDuffie and artist M.D. Bright that make the hero his own. Unlike Superman, Icon first crashed in the United States as an adult. Unlike Superman, it was hundreds of years ago, long before the abolition of slavery. Unlike Superman, Icon had black skin. And unlike Superman, when the reclusive Icon is finally urged to use his powers for good in the modern age by teenager Raquel Ervin, his Blackness brands him as a threat and enemy to law enforcement on sight. The conversation Richard Pryor had begun in 1968 was now in the comics themselves, and it was deadly serious. In Icon, McDuffie and Bright showed us that the idea of a Black Superman isn’t just a difference in pigmentation, but one which carries massive cultural baggage.

One month after Icon’s debut, a Black Superman arose in the DC Universe as well. Superman himself had just fallen in battle against the alien monster Doomsday, and four new heroes emerged to fill the void. There were genetic heirs, visual duplicates, and those who wielded his exact powers. But only one man wore the S shield without claiming to be the “real” Superman, instead choosing to earnestly continue Superman’s mission in his name. That was engineer John Henry Irons, who built himself a suit of armor, forged a powerful kinetic hammer, and called himself the Man of Steel. Other pretenders bore Superman’s face, but to Lois Lane, only Steel carried Superman’s heart. Even after the original Superman returned, Steel was given his own spinoff series which ran for 54 issues and has remained a valuable ally and a figure of stature in the DC Universe to this day.

1994-1997: The Man of Steel

In 1994, the mononymed comic writer Priest became the first Black writer on a Superman comic, Superman: The Man of Steel Annual #3. Three years later, Priest would become the first—and, to date, only—Black writer with an ongoing role on a title in the Superman family as well, writing Steel #34-52.

The same year that Priest took over Steel, DC first presented a Black Superman on screen—at least, of sorts. At the time, basketball player Shaquille O’Neal was experiencing a Muhammad Ali-level of fame and recognition as an athletic icon, so nobody was going to say no to his movie star dreams. And at 7’1, you could say that Shaq was quite literally Superman’s biggest fan. So, the Big Daddy of Basketball was suited up to star as Irons in an original movie, with all but the S crest on his chest.

1997 was also the year of DC’s experimental Tangent Comics project, a line of comics which completely reimagined the entire DC Universe by removing every recognizable element but the character names and branding. What does a character named “The Joker” mean if we removed every preconceived idea we had of that character? What about the Flash? Or Green Lantern? Or Superman? For Tangent, writer Mark Millar reinvisioned the character as Harvey Dent, a Black man undergoing a Kafkaesque metamorphosis and driven to madness by his power. If nothing else, it was the first time that a Black character named “Superman” had his own comic.

1998: Dial “D” For Diversity

The next year, a special issue of Legends of the DC Universe, a series exploring untold chapters of importance and significance in DC history, revisited the Crisis on Infinite Earths. It was here that Barry Allen discovers “Earth-D,” a world very similar to the DC Universe of the Silver Age, but with a more racially diverse and equitably represented Justice League of America, here known as the “Justice Alliance.” The Justice Alliance had an Asian Flash, a Native American Green Arrow and a Black Superman, who here was married to a Black Supergirl. (Presumably, we would hope, she was not his cousin on this Earth.) Batman, for some reason, was still white. The Legends of the DC Universe: Crisis on Infinite Earths Special tells the story of the Justice Alliance’s last stand against the Anti-Monitor, evacuating millions from their world before facing annihilation. Like all the worlds destroyed in the Crisis, Earth-D and its Justice Alliance would be restored in 2015’s Convergence and recently joined the DC Animated Universe with an appearance in the in-continuity Justice League Infinity.

2005: Children of Vathlo

Throughout the 2000s, when you were talking about Superman, you were probably talking about Smallville, the record-breaking TV series telling the ten-year story of Clark Kent’s tightless, flightless journey to the role of Superman. It was a version of Superman’s story that wasn’t afraid to shake a few things up, with a young Clark getting acquainted with many of the characters and elements which would define his tenure as Superman long before he wore the crest. In 2005, Clark was meeting other survivors of Krypton’s destruction, including the fugitive “Disciples of Zod.” One of these disciples, Nam-Ek, was played by Leonard Roberts, making him the first Black Kryptonian on television. The concept of a Black Kryptonian population introduced by Bridwell back in 1970 was finally starting to pay off.

2009: President Superman

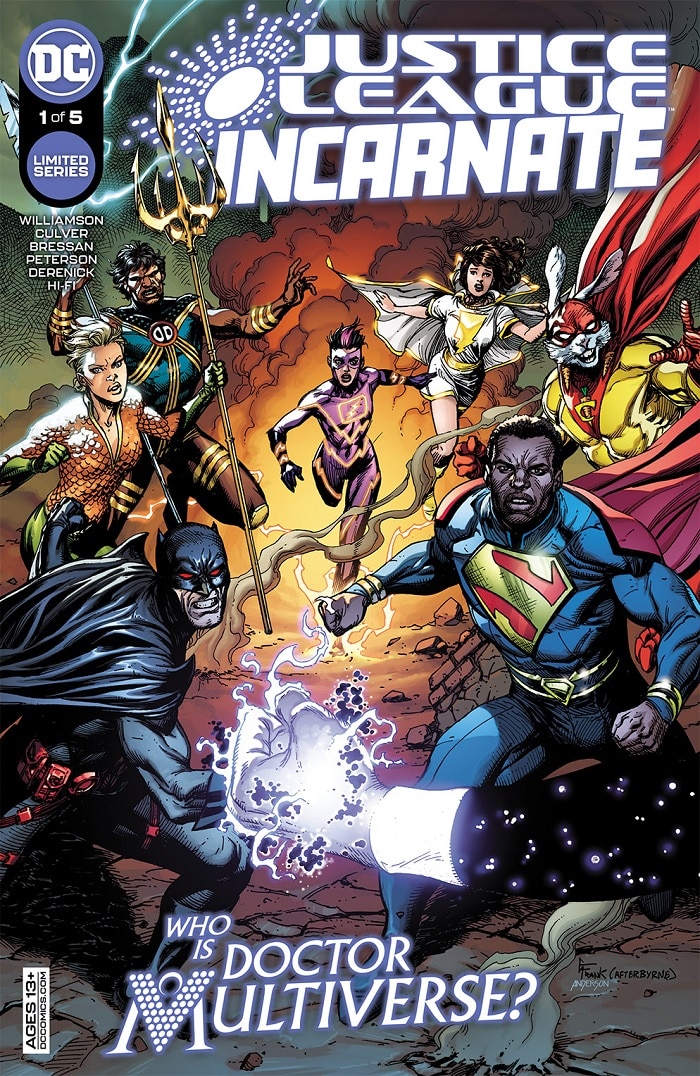

The most well-known of all incarnations of Black Superman debuted in Final Crisis #7, by Grant Morrison and Doug Mahnke. In a story where all the Supermen of the Multiverse converge in a stand against Darkseid, we came to know Calvin Ellis, the Superman of Earth-23. Ellis, on his world, was no mere mild-mannered reporter, but President of the United States of America.

The parallels to Barack Obama, our nation’s first Black president who had begun his term that year, are obvious. But according to Morrison, Calvin Ellis was also inspired by the looks and personality of Muhammad Ali, who had proven himself Superman’s equal three decades before. Today, President Superman is one of the most essential guardians of the Multiverse, as de facto leader of the Justice League Incarnate, which stands to protect all worlds across reality.

2011: Loss of an All-Star

If anything, it would be an understatement to call Dwayne McDuffie a genius. In his short time, Dwayne changed the face of comics forever, as the spearhead of Milestone Media and a central figure in the DC Animated Universe projects of Static Shock and Justice League Unlimited. McDuffie dedicated his brilliance not just to a higher quality of stories for readers and viewers, but to a greater diversity of voices to be heard through comics and animation alike.

On February 21st of 2011, the world lost Dwayne McDuffie far, far too soon, due to complications from an emergency heart surgery. But McDuffie did leave the DC Universe with one final gift: his adapted screenplay of Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s All-Star Superman, considered by many to be among the greatest Superman stories ever told. McDuffie’s adaptation of All-Star Superman was released as an animated film just one day after his death, securing one last milestone on his way out. Dwayne McDuffie would be the first Black writer of a Superman film.

2014-2018: Legacy of Zod

When the comic book universe was rewritten in 2011’s “New 52,” one of the biggest changes was to the DC Universe’ next door neighbor, “Earth 2,” a world where Golden Age heroes were now reimagined through a modern lens, and where Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman had all fallen to the army of Darkseid. In their place, new wonders arose to protect the planet as Apokolips returned once more. One of these was Val-Zod, another refugee from Krypton, who takes up Superman’s crest for the fallen hero and continues his work on Earth.

It wouldn’t be the last time the name of Zod was applied to a family of Black Kryptonians. In the Syfy series Krypton, Superman’s grandfather Seg-El has a romantic affair two hundred years before the planet’s destruction with Lyta-Zod, played by Georgina Campbell. Their romance is interrupted by none other than General Zod himself, played by Colin Salmon, traveling back in time from our present to prevent Krypton’s destruction. Eventually, Zod is revealed to be the child of their passion, and therefore Superman’s uncle.

2022 and Beyond: The Black Superman of Tomorrow

Through the past ten years we’ve had Black Supermen in comics and Black Kryptonians on television. President Superman currently stars in Justice League Incarnate, one of the most important books to modern DC continuity as a whole. Last year, we learned that two more significant Superman projects were in development: a theatrical treatment being written by Ta-Nehisi Coates, which would be the first live action Superman film from a Black writer; and a “Black Superman” project for HBO Max, produced by Michael B. Jordan. To be clear, these projects, like most of the breaking news coming out of Hollywood, are in very early stages and there’s no guarantee they will go before cameras. But here’s what we can say for sure. As far as the search for a Black Superman has come since it was recorded at a comedy club in 1968, the journey isn’t over yet. Come along with us and perhaps we’ll make it together.

Click here for part one of our feature on the Black History of Superman.

Alex Jaffe is the author of our monthly "Ask the Question" column and writes about TV, movies, comics and superhero history for DCComics.com. Follow him on Twitter at @AlexJaffe and find him in the DC Community as HubCityQuestion.