If you haven't taken a look back at WATCHMEN in a while, you might have forgotten about the slightly non-sequitur pirate stories that pepper the whole event. They're called "Tales of the Black Freighter" and if you're anything like me, your first encounter with them was probably a little bit confusing. After all, what does a pirate comic have to do with a nuclear man and a megalomaniac bent on saving the world by destroying it?

But if you pause to think about the Black Freighter stories, you'll quickly realize they're actually an important bit of world building. Fiction existing within fiction is a pretty tried-and-true method of fleshing out a universe, and, as writer Alan Moore explained, a world where superheroes actually exist wouldn't have much use for superhero comics, so pirate comics just start to make sense. However, if you dig a little deeper than that surface bit of detail work, you can start to find all sorts of interesting parallels and connections between the Black Freighter strips and the actual Watchmen narrative.

I mean, really, the way Veidt talks about how he's having "trouble dreams" where he’s drowning and swimming? Watchmen fans have worked tirelessly at examining “Tales of the Black Freighter” over the years. It’s adds a whole new dimension to the Ozymandias narrative.

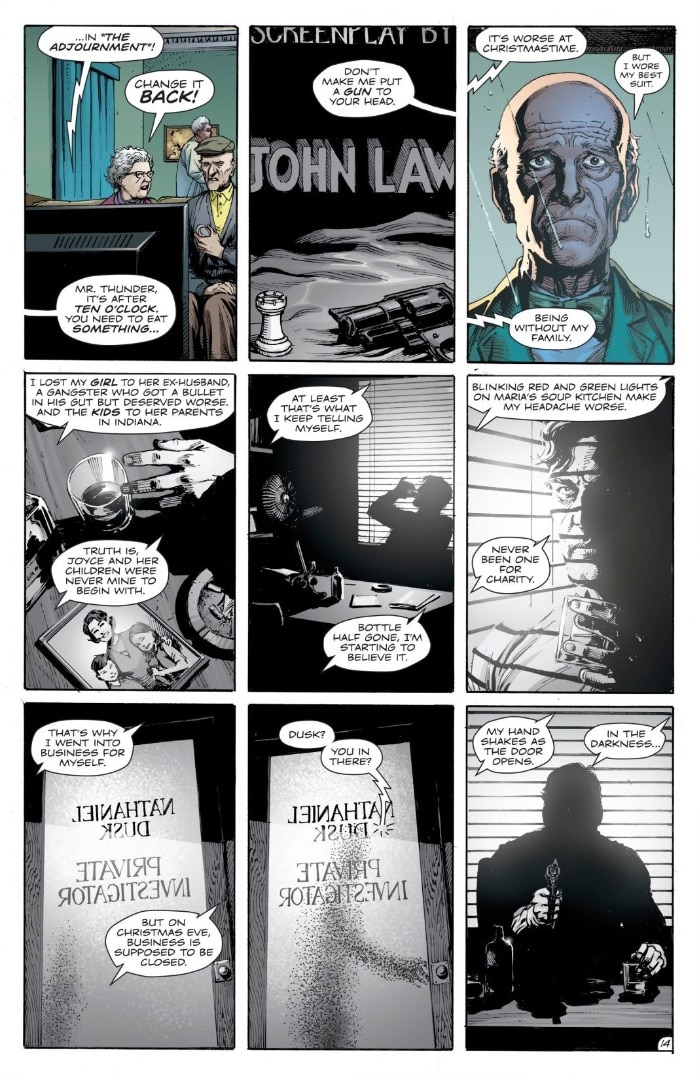

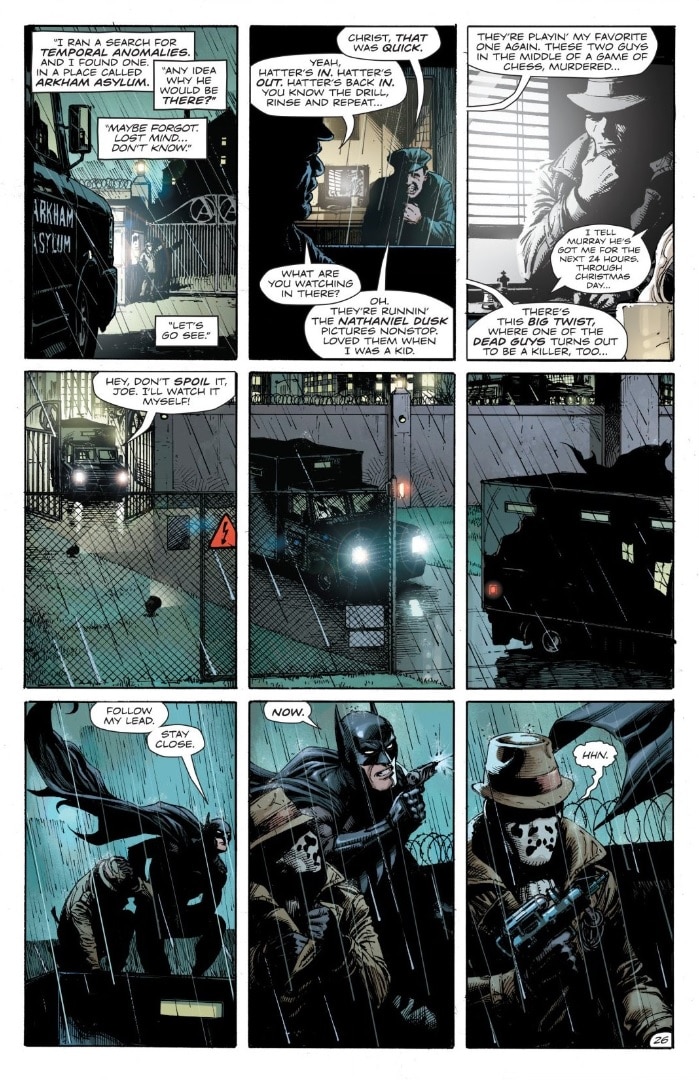

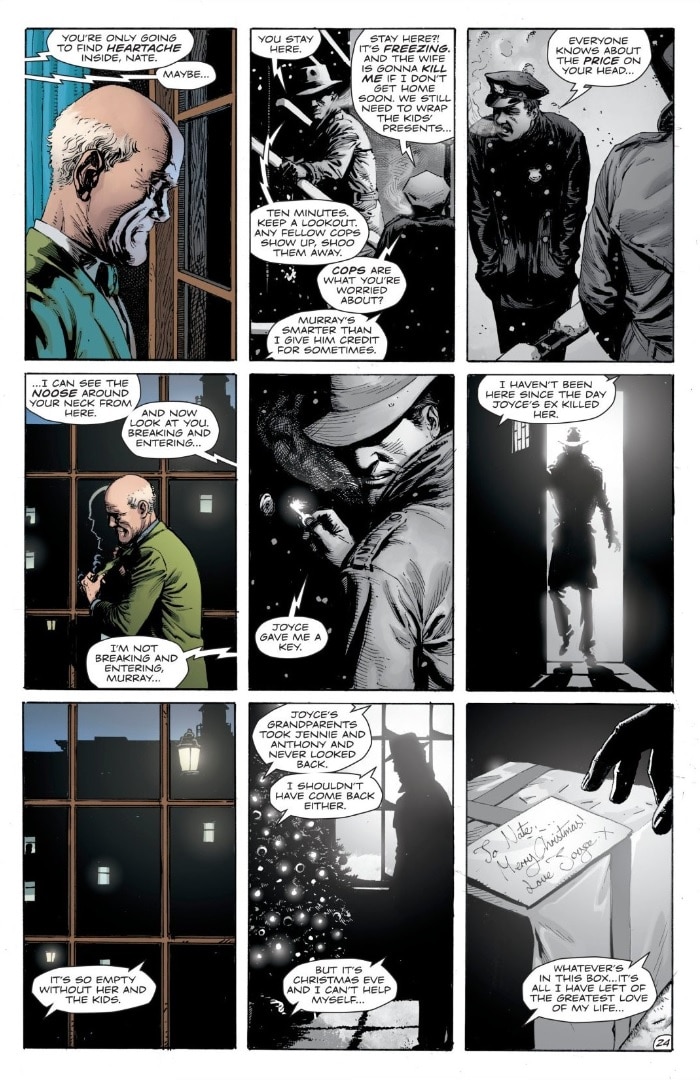

This week, DOOMSDAY CLOCK #3 introduced a similar element all its own—a fiction set within the fiction, but with its own unique twist on the idea. After all, we've traveled from the Watchmen world over to the DC Universe proper, so there are no pirate comics to be had. Instead, here, in the world we're more familiar with, we've got black and white films. Or, more specifically, the vintage "film noir" flavored movies of an actor named Carver Coleman as he plays Nathaniel Dusk, a fictional investigator (and call back to a very old DC Comics character—some meta for your meta.)

Both the Coleman films and the Black Freighter comics rely heavily on very similar techniques, because like you probably could have guessed, there's a little more to it than just making sure a panel includes a person reading a comic or watching a TV. Comics, like film, television, or any other image-based media, use something commonly referred to as "visual grammar" when telling stories. Moments of fiction-within-fiction are an extension of that grammar; part of the system of rules in place to make sure that we, the reader, can interpret everything being put down on the page or on the screen in the way that the creators intend, even if we don't realize what it is we're seeing at first. The visual grammar of comics informs everything from how we perceive motion and speech in still panels to how we understand less literal things like the passage of time or even the lack thereof. If you've been reading comics for a while, all of this becomes second nature, so it's actually pretty easy to just breeze right by without a second thought.

As a result, Doomsday Clock's use of old film noir might actually be something you glossed right over. After all, just like the Black Freighter comics, the Coleman films don't exactly have neon signs pointing to them on the page. They're one part visual metaphor—representation of a concept, character or idea with an image—and one part montage—the intercutting and overlaying of two completely different moments in time on top of one another for dramatic or symbolic effect.

Dialogue from the Coleman films splashes out into the "real" world, encroaching on both Rorschach as he explores Wayne Manor and Johnny Thunder as he sits in his nursing home. Just like the lines between the Watchmen universe and the DC Universe have been smeared together, the gaps between the story unfolding in the movie and the story unfolding for our heroes are fuzzy and shifting. This effect gets even more pronounced as the Coleman film takes over whole panels on the page, dominating spaces in the nine panel grids in its full black and white glory, almost as if the story in the movie is happening simultaneously and in real time with the events happening in the comic itself.

The visual links are pretty easy to spot, too, once you slow down to see them. Johnny Thunder adjusts his jacket as he turns away from the window in a mirror image of Nathaniel Dusk on screen, all while the dialogue in his panel is populated from the off-panel TV. A voiceover from the movie, "there's nothing else but memories," bleeds into a flashback of Rorschach's as he remembers the monster attack on New York City. You get the idea. This intercutting and use of montage is painting layer after layer onto the story, just waiting for you to slow down and notice it.

The real question is, if Carver Coleman's Nathaniel Dusk movies are telegraphing more than just world building, if they are working like the Black Freighter comics and connecting to one specific character's arc the way Watchmen's pirate comics came to represent Ozymandias, whose story are we meant to be seeing? And just where is it going to end?

Meg Downey writes about the DC Universe for DCComics.com and covers Legends of Tomorrow for the #DCTV Couch Club. Look for her on Twitter at @rustypolished.

DOOMSDAY CLOCK #3 by Geoff Johns, Gary Frank and Brad Anderson is now available in print and as a digital download.