Every year, DC has been doubling up its mission statement of LGBTQIA+ inclusivity for DC Pride. More queer characters, more queer stories, presented by more queer creators from a wider variety of perspectives. It’s a commitment which invites those disenfranchised by a frequently homogenized status quo to realize that none of us are alone, and even our historically buried narratives share resonance with each other in the light.

Queerness has been part of the DC story since almost the very start of its comic book history, shaped as all things are by the issues, perspectives and attitudes of the time. Because of this, comics, like all literature, function not just as entertainment, but as historical documents. How DC has utilized queer characters and themes says much about the social context in which they appear, opening a window into the challenges and pressing issues facing the queer community at the time they were published. Through a history of queerness in DC comic books, we get a snapshot of the attitudes towards LGBTQIA+ communities and themes through the 20th and 21st centuries at large.

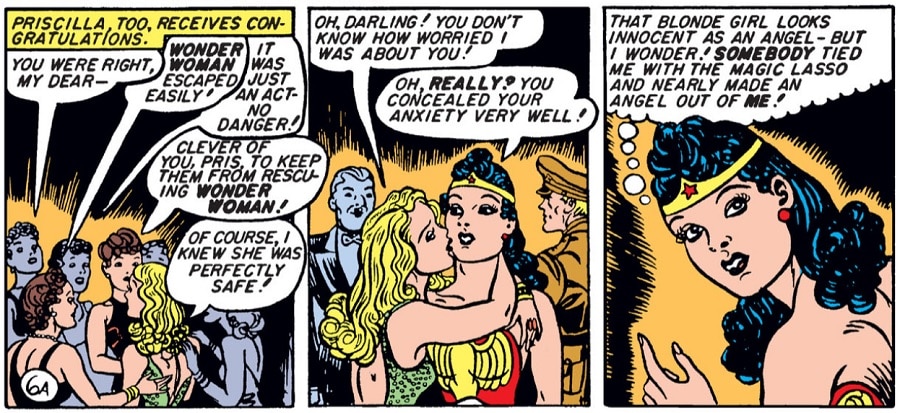

One of the earliest comics to challenge the roles of gender and sexuality in 20th century America was William Moulton Marston’s Wonder Woman, which presented a society of Amazon women who freely exchanged love with each other as an alternative to engaging in mankind’s proclivities for war. Marston, himself in a polyamorous relationship with two women, proposed that after millennia of letting men run the world, it might not be too bad an idea to let women have a go of it. Although somewhat coded, the messaging of love beyond heteronormativity in Marston’s Wonder Woman was obvious to anyone paying attention—and, indeed, was picked up on by pop psychologists who used it as evidence to condemn comics as a medium for promoting what was seen as aberrant behavior. In response to this and other comic book controversies of the time, the Comics Code Authority was formed, suppressing overt queer themes in comics for a generation.

One of the first opportunities for DC to address themes of sex and sexuality in comics overtly would be in the birth of Vertigo Comics in the late 1980s. And while it’s usually left out of discussion about the history of DC Pride, one of the most radically queer comics of the 1980s is also considered by many to be one of the greatest comic runs ever written to this day.

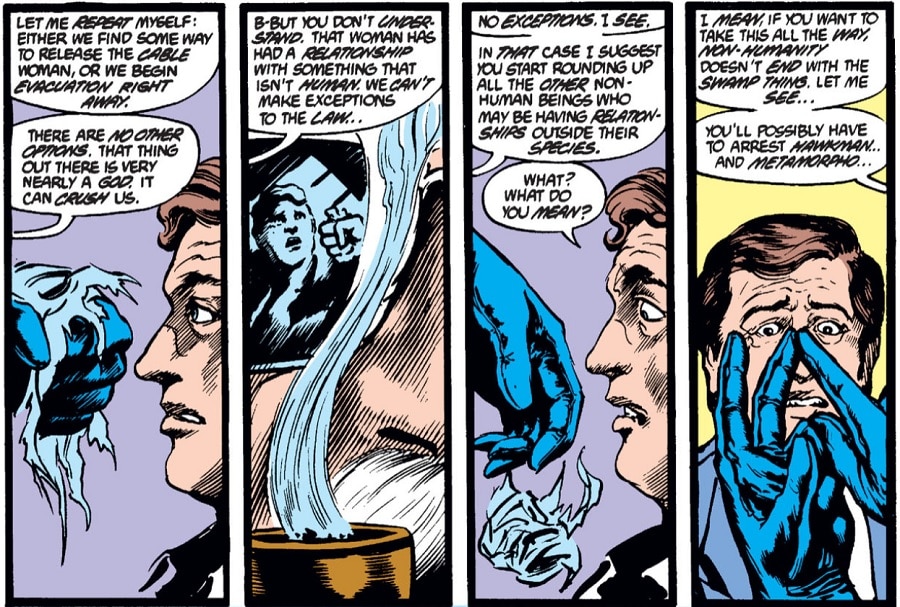

Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing is one work in a bibliography of stories standing for queer rights against a British government, which at the time was continually enforcing and passing legislation to criminalize homosexuality. Moore’s Swamp Thing, in its scope and inventiveness, is considered one of the greatest works in the comic medium. But what modern readers miss is the allegory that lies at its heart: that the romance between Abby Arcane and the Swamp Thing himself is meant to stand for all romance that people from the outside can’t understand. It’s an allegory written for straight people, essentially, about queer love. The message is this: it doesn’t matter if you don’t understand why two people love each other. Interfering with love, no matter what form that love takes, always makes you the monster.

At the same time, Doom Patrol was reinventing itself to reinforce the queer themes that have always been inherent in the double lives and traumatic origins common in the superhero genre. In presenting both allegorically resonant trans experiences through the perspective of Robotman, and literal ones in heroes like Coagula of Rachel Pollack’s Doom Patrol, this revival of the “world’s strangest heroes” illustrates that just as comics have been forced to hide their queer themes, so too have queer people by banding together under a judgmental social eye. In the face of bigotry and queerphobia, through queer communities do queer lives survive.

Only when comics began directly acknowledging that queer people exist could they also begin to acknowledge the issues they faced. The HIV epidemic was such a gargantuan tragedy that it was impossible to circumnavigate. You couldn’t talk about being queer without the terror that came from knowing every day, you could wake up to hear the news that another person you held dear had been suddenly lost.

Some stories handled this more elegantly than others. HIV awareness gave us Extraño, who we now recognize as the first openly queer superhero. It also gave us the multiple GLAAD award-winning narrative of Terry Berg, a young intern to Green Lantern coming to terms with his own sexuality. Terry was inspired by creator Judd Winick’s friendship with his Real World: San Francisco cast member Pedro Zamora, one of the first openly gay men on mainstream television and an AIDS awareness advocate who passed away in 1994. His story was all too common. It was clear that queer issues could no longer afford to be ignored, and stories like Terry Berg’s could play a part in normalizing them in open conversation.

In 2002, The Authority ended its initial run with a wedding between its Batman and Superman surrogates, Midnighter and Apollo. Today, when marriage equality is legal in all fifty US states, it’s easy to forget how radical an image this was at the time. The context is often lost that the wedding was held in space, beyond the borders of laws in place making gay marriage illegal. It was only in this year’s DC Pride that the pair recommitted to each other on Terra Firma, this time for all the world to see.

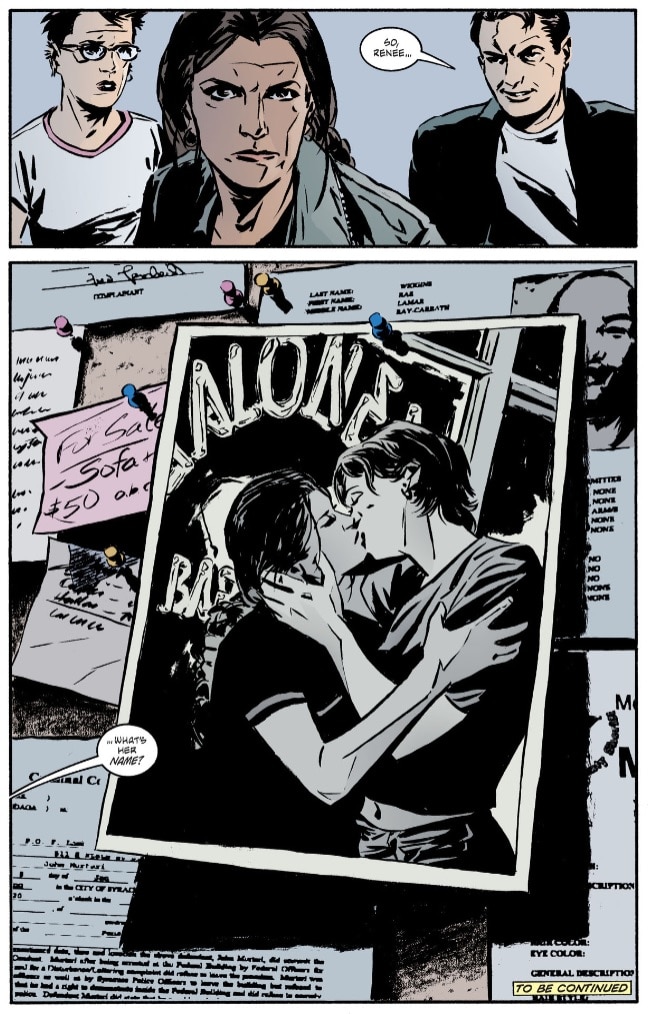

As we entered the 21st century, writer Greg Rucka gave us a duology of coming out stories which painted a stark picture of how authority responds to queerness. In Gotham Central’s “Half a Life,” Renee Montoya is outed to her peers at the Gotham City Police Department as a closeted lesbian. Her coworkers, and her family, never see her the same way again. It would be nice to say that Montoya’s life got better after that, but it’s only after leaving the police behind her that she’s able to find some self-acceptance.

Some years later, Rucka’s Batwoman comes to a similar conclusion. Under the auspices of the now repealed “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, star military cadet Kate Kane confessed to her superiors that she was gay and was immediately dismissed from service for her honesty. In doing so, Kate was able to take charge of her own identity and reinvent herself on her own terms.

In 2021, we saw the publication of the first DC Pride anthology, now an annual tradition which kicks off a new year of commitment not just to queer characters, but the enlistment of queer writers and artists to tell those stories themselves. DC Pride is an annual call to action for stories like Crush & Lobo, Spirit World and the upcoming Bad Dream: A Dreamer Story to present a wider, authentic view of the queer experience from those who have lived it. Like Terry Berg in Green Lantern, like Renee Montoya and Kate Kane in Gotham City, characters like Galaxy in Galaxy: The Prettiest Star also illustrate the risk that our queer youth still takes when they present their true selves to the world. It’s not always easy. In fact, these stories are often brutally honest about the reality we face—that in a world where hate and prejudice remains alive, you are going to face it when you defy expectations. But when you do, the reward is so much greater. The world has far more joy to offer than pain. And now, you can trust the people who tell you. They were there.

How future developments in the queer community will influence comics and superheroes to come, no one can say. But the issues that writers like Alan Moore fought for in real life and in allegory are still on the line. Legislation bringing LGBTQIA+ communities under attack is still being passed by bigoted groups in the United States and abroad. Through comics like DC Pride, DC is still doing its part to bring attention to the personhood and validity of queer lives at stake, and to illustrate to our readers that they will never be alone. Comics reflect the world by showing us that heroes are still alive. And just through the radical act of self-acceptance, you can count yourself among them.

Alex Jaffe is the author of our monthly "Ask the Question" column and writes about TV, movies, comics and superhero history for DC.com. Follow him on Twitter at @AlexJaffe and find him in the DC Community as HubCityQuestion.

NOTE: The views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of Alex Jaffe and do not necessarily reflect those of DC Entertainment or Warner Bros., nor should they be read as confirmation or denial of future DC plans.