In 2003, during the invasion of Iraq, the Fedayeen Saddam troops took up defensive positions surrounding the Baghdad Zoo as U.S forces began the Battle of Baghdad. The zookeepers abandoned the facility and by the eighth day of the invasion, only 35 of the original 700-something animals remained. Some were still caged and starving, others had been freed by bombs and were roaming the streets of the abandon cities. When they would not be wrangled back into their cages, four lions were shot by American soldiers.

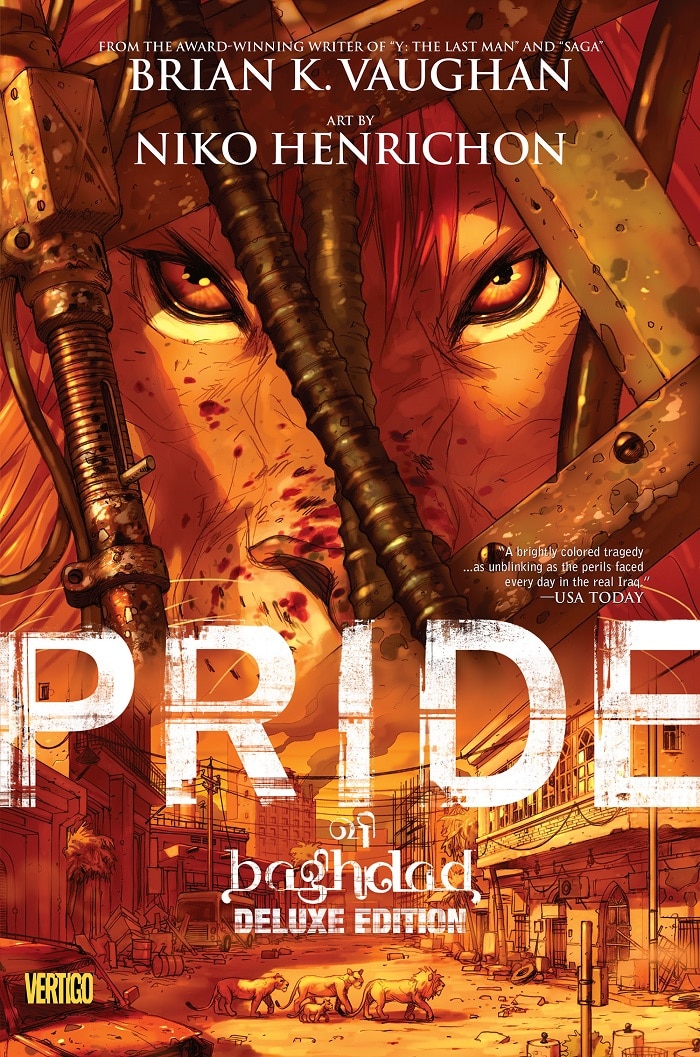

Three years later, Brian K. Vaughn and Niko Henrichon’s PRIDE OF BAGHDAD was released, a fictional story of the liberation and subsequent death of those four lions.

After the first air raid, the lion pride of the Baghdad Zoo find themselves finally free in the empty city of Baghdad, where they explore the lives of the humans who lived there, questioning their own along the way.

Graphic novels often walk the knife’s edge of art and entertainment. Oftentimes you’re getting a bit of both, but with Pride of Baghdad, you are certainly getting something more in the artistic vein of George Orwell’s Animal Farm.

The first time I sat down to read this book, it was right before the most recent election year, but within three pages found myself in need of something that leaned more towards entertainment; political fatigue had won out. I didn’t want to read something that was going to teach a thing at me.

But when I mentioned this to my peers, I discovered that was the reason a lot of them had also never read the graphic novel before. The common response was that they wanted to sit down and be emotionally ready for a sad, political book. The sense that lingered amongst us all was that the experience of reading the novel was going to be a beautiful, well-crafted chore.

Experiencing art should never be a chore. So, I guilted myself into going back and giving it the good ol’ college try.

I am so glad I did.

Sitting down recently and really, really digging into Pride of Baghdad showed me the difference between teaching and feeling something important. It is a reminder that if you sit down and give it a chance, a politically charged graphic novel can genuinely change how you see a situation.

What struck me first about Pride of Baghdad is Brian K. Vaughn’s eloquent use of beast fablism.

The idea of telling a moralistic story by using animals as allegories is not new to us. It is a device dating back hundreds of years, across over a dozen cultures, and it still used quite effectively today. Animal Farm is the obvious reverence, but any Pixar film will prove this point. Beast fables are a powerful way of experiencing wonder and innocence before tearing it all to pieces with the intricate philosophies of mankind.

The four lions of the book are each symbols of common political perspectives in Iraq under Saddam Hussein’s regime at the time of the invasion. Safa is the elderly lioness who has become accustomed to the regime of their captors (or keepers)—it offers safety, multiple meals a day and fresh water. One blind eye and a torn ear indicate that she remembers a savage time of hunting and being hunted. Noor, a younger lioness, longs for freedom from their keepers, attempting to talk to other factions of animals to stage a revolution within their midst. Her and Safa often argue that she does not remember what it was like before the keepers, and that her notion of freedom is not as perfect as it may seem. Ali, the young cub of Noor and a child born in captivity, is thrilled by the notion of a promised better world. An ignorant optimist, he is too innocent to hate what he has, or to realize how change is begot. And finally, Zill is the middle-aged alpha male, sitting on the fence between his two lioness lovers. He wistfully wishes for certain moments of the freedom he once had, but feels too soft and fatigued to fight anymore.

The ultimate question that lingers between these four comrades remains throughout the novel: is it better to be fed and caged, or to be free and hungry?

The other animals they encounter continue this sense of fablism, as well.

During their escape from the zoo, Ali is captured by the inhabitants of another recently freed cage: a roving band of monkeys. In the wake of an explosion, they lie to him, saying that his parents are dead and that he is now one of their own. They express very openly that he will be seen by other animals as a symbol of their group’s power. The monkeys proceed to try to slice a brand into Ali to mark him. They see Ali as a captured child solider to be molded in their image, striking fear into the hearts of their enemies by the idea that he, a child of great predators, could be tamed to their will.

After their escape, the lion pride encounters an elderly sea turtle who speaks to them of the price of all war. Over a hundred years old and a witness to the atrocities of man across time, the turtle has lost his wife, children and friends to these ongoing conflicts. This notion is accompanied by a memory panel of sea turtles, birds and other river creatures, drenched and dead amongst a driving cause of war in the region: oil. Henrichon really asks the audience for this brief moment to think of the civilian casualties of this ongoing conflict. They want nothing to do with the wealth that comes of victory. They just wish to live.

What’s so fascinating about what Vaughn manages to do with these allegories is that he manages to weave the savagery of the animal kingdom into the savagery of the characters’ human representations. The animals are more human than we give them credit for, but we as humans are more savage than we think.

Cats do not mate for fun. It is a primal instinct that females do not enjoy, and they show that through a scene from Safa’s past. It gives great context for an older woman who has seen the savagery of a world without order, and the very personal trauma it inflicts, while showing a very natural part of being a member of the animal kingdom.

Fajer, a great black bear, is found chained to a wall in a grand palace beside a dying male lion. The imposing creature explains that the animals are pitted against each other for entertainment, and that he steals his opponent’s food. This is not only an allegory for the perversion of socialist ideals by a system of wealth and monarchy, but a very, very base instinct animal thing to do. Only the strongest survive.

The other thing that will instantly catch your eye about Pride of Baghdad is the genuinely gorgeous art depicting the sumptuous beauty of a place that was often portrayed on the news as a bombed, desert wasteland of a city.

Henrichon really does a magnificent job of capturing the vibrant life of a desolate, but once decadent modern city. In each new area the characters encounter, they are met with brilliant color and stunning opulence; from the nearby jungles, to the monumental Swords of Qādisīyah. Panel by panel, he forces you to feel not just for the animal inhabitants, but for the loss of a beautiful city you have never seen.

Pride of Baghdad is not the kind of piece that lets you marinate from panel to panel. It strikes you, like the swipe of a lion’s paw. It strikes at your heart, your eyes and your mind, begging you to see war the way an active participant would: quickly and on your feet. It is not just a sad and provocative piece, it evokes true heart through its characters, their circumstance and the beauty that surrounds them despite the devastations of a war-torn scape.

Now that I’ve finally read it, I plan to reread this book often as a reminder of what we can do with comics. There is a power to this type of visual storytelling, and it is on the finest display with Pride of Baghdad. If you’ve been waiting to read this, run, don’t walk.

PRIDE OF BAGHDAD by Brian K. Vaughan and Niko Henrichon is available in print as a deluxe edition and as a digital download.